Trial-history Biases In Evidence Accumulation Can Give Rise To Apparent Lapses In Decision-making

Abstract

Trial history biases and lapses are two of the most common suboptimalities observed during perceptual decision-making. These suboptimalities are routinely assumed to arise from distinct processes. However, previous work has suggested that they covary in their prevalence and that their proposed neural substrates overlap. Here we demonstrate that during decision-making, history biases and apparent lapses can both arise from a common cognitive process that is optimal under mistaken beliefs that the world is changing i.e. nonstationary. This corresponds to an accumulation-to-bound model with history-dependent updates to the initial state of the accumulator. We test our model’s predictions about the relative prevalence of history biases and lapses, and show that they are robustly borne out in two distinct decision-making datasets of male rats, including data from a novel reaction time task. Our model improves the ability to precisely predict decision-making dynamics within and across trials, by positing a process through which agents can generate quasi-stochastic choices.

Introduction

It has long been known that experienced perceptual decision makers deviate from the predictions of optimal decision-theory, displaying several suboptimalities in their decision-making. Among the most pervasive of these is the dependence of behavior on the recent history of observed stimuli, performed actions, or experienced outcomes, despite it being disadvantageous and leading to worse performance1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18 (schematized in Fig. 1a top). History biases may arise due to a strategy that is optimized for naturalistic settings, where continual learning of priors, action-values, or other decision variables helps agents adapt to changing environments, but is maladaptive in experimental settings where the statistics of the environment are stationary19,20. To date, decision-theoretic models have accommodated history biases by modeling them as a biasing factor on the perceptual evidence that drives choices3,12,13,21,22,23,24,25,26. In the predominant conceptualization of these models, history biases can be overcome with sufficient perceptual evidence.

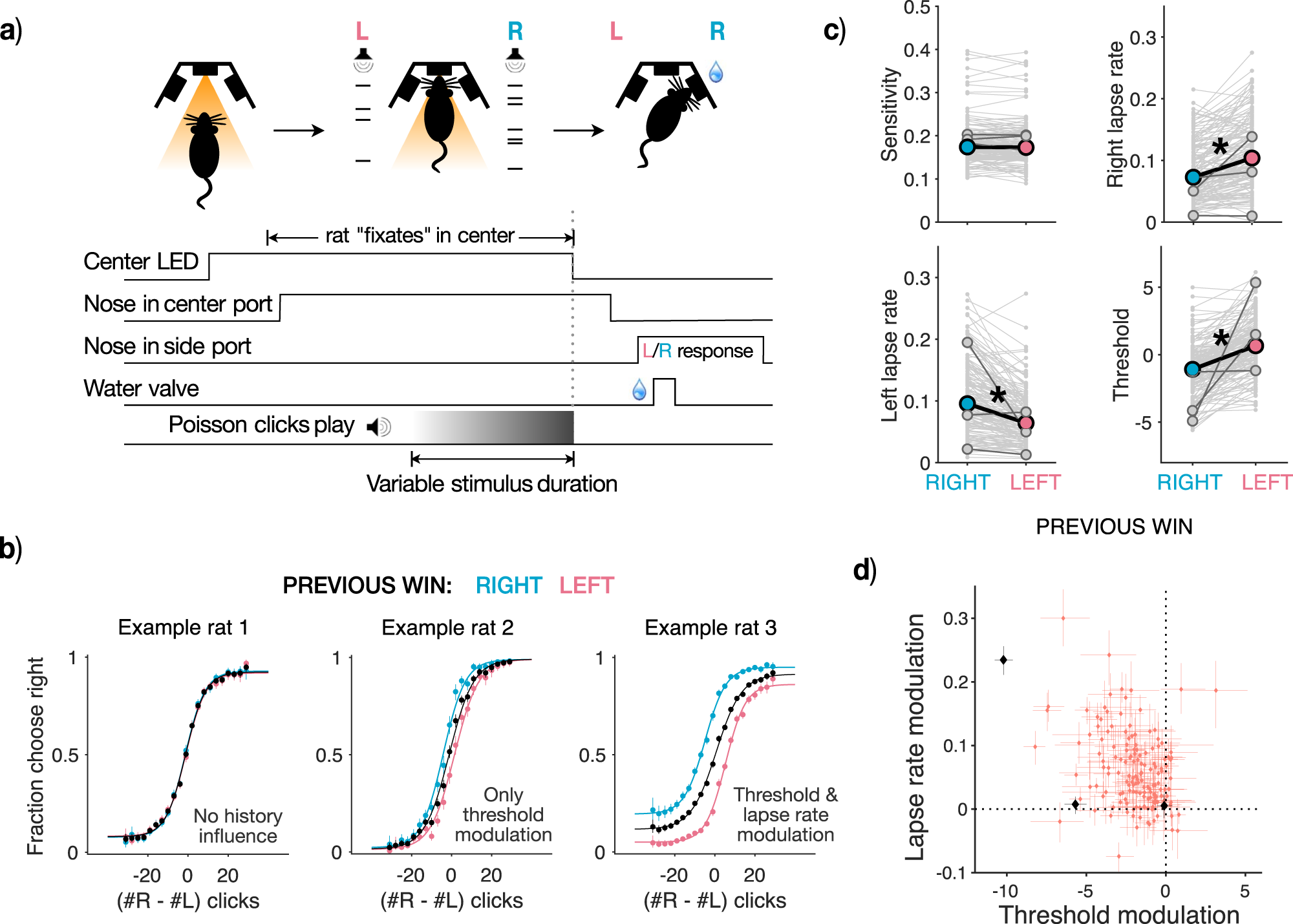

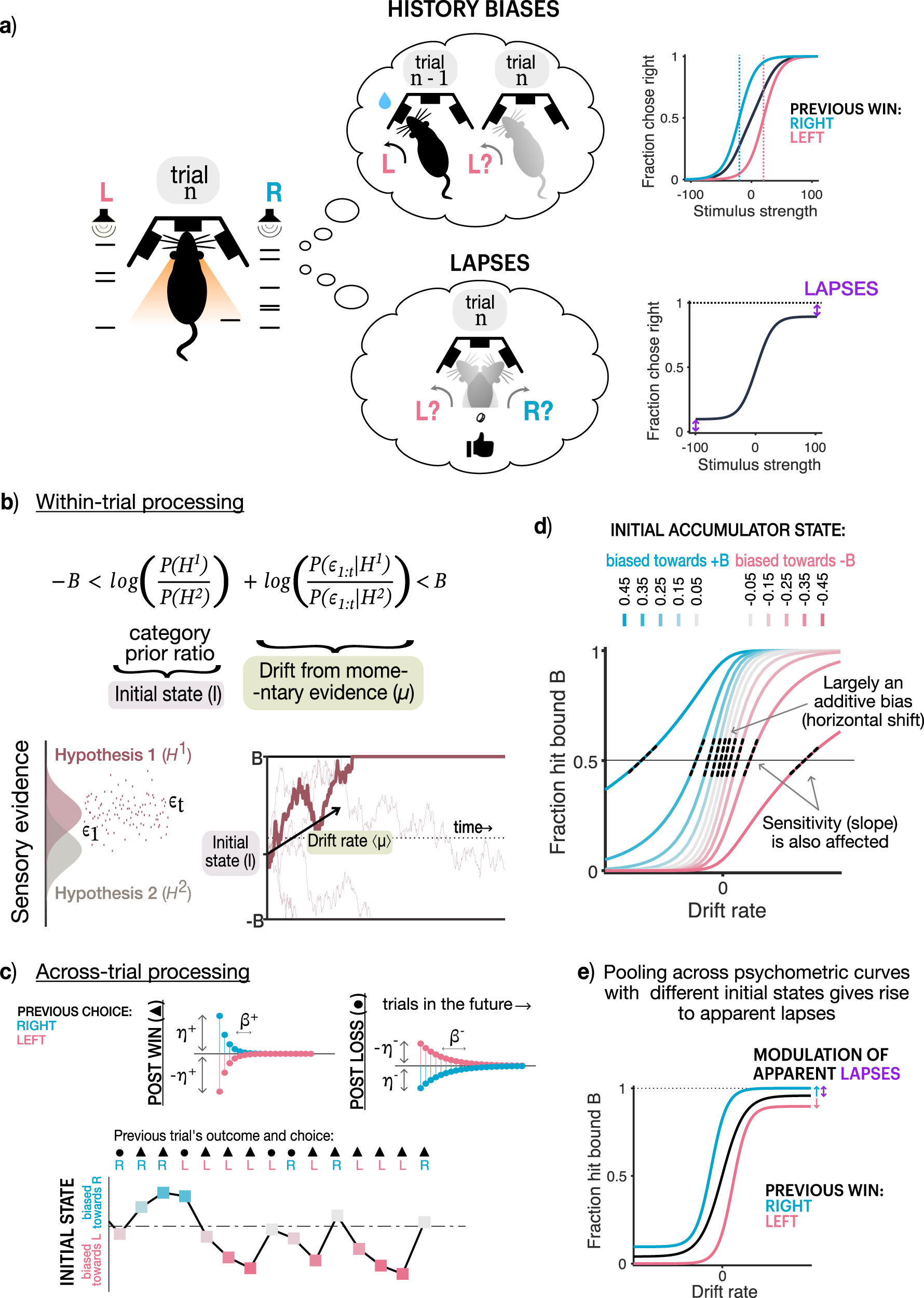

a Schematic of two common suboptimalities: history biases (top) and lapses (bottom). (Left): Rat making one of two decisions (left, right) based on accumulated sensory evidence (clicks on either side). (Top left): History biases i.e. an inappropriate influence of the previous trial (n-1) on the current decision (n) in addition to sensory evidence. (Top right): Typically assumed effect of history bias on the psychometric curve, shifting it horizontally around the inflection point. (Bottom left): Lapses i.e. a tendency to make seemingly random choices irrespective of sensory evidence. (Bottom right): Typically assumed effect of lapses on the psychometric curve, vertically scaling its asymptotes (Figure adapted with permission from Bingni W. Brunton et al., Rats and Humans Can Optimally Accumulate Evidence for Decision Making. Science 340,95-98(2013). DOI:10.1126/science.1233912) b Normative model of within-trial processing. (Top) Optimal decision rule that chooses when the summed log-ratios of priors and likelihoods exceeds one of two decision bounds, corresponding to a drift-diffusion process. (Bottom left): Generative model, where one of two hypotheses (H1, H2) produce noisy evidence over time (ϵt). (Bottom right): A sample trajectory based on noisy evidence (bold line), and alternate trajectories (thin lines) based on noisy instantiations of the same drift rate (black arrow). c Model of across-trial processing that accommodates prior updates. Past choices and outcomes can affect the initial state with different magnitudes (η) and timescales (β) depending on whether they were wins/losses (top left/right). (Bottom): Example trial sequence ans corresponding initial states following previous wins (triangles) or losses (circles) on right (R) or left (L) choices. Colors denote initial state biases, towards positive (blue) or negative (pink) bounds. d Effect of initial state values on psychometric curves. Colors same as c. Small deviations in initial state (grey) lead to largely horizontal biases whereas larger deviations (saturated colors) additionally reduce its effective slope (dotted black lines) or “sensitivity" to stimulus. e Pooling psychometric function (black) across trials with different initial state biases gives rise to apparent lapses (purple arrow). Conditioning the curve on previous rightward (blue) or leftward (pink) wins reveals a modulation of apparent lapses by trial history.

A second widely-recognized but less studied suboptimality is the tendency to “lapse", or make (asymptotic) errors that are immune to strong evidence3,4,11,27,28,29,30,31,32,33 (schematized in Fig. 1a bottom). Because lapses appear to be evidence-independent, they are assumed to arise from nuisance mechanisms that are separate from the perceptual decision-making process and are often imputed to ad-hoc noise sources such as inattention, motor errors etc.

However, several recent results suggest that these two suboptimalities may be linked in their origin. In primates, learning reduces dependence on recent trial history2 as well as lapse probabilities28. Intriguingly, mice trained on a visual detection task showed higher levels of history dependence on sessions with higher lapse probabilities3. Moreover, lapses occur in runs (i.e. display Markov dependencies), rather than occurring with the traditionally assumed independent probabilities across trials34. Furthermore, lapses have been proposed to reflect forms of exploration32 that are sensitive to trial-by-trial updates of variables such as action value. Likewise, neural perturbations of secondary motor cortex and striatum in rodents have been shown to substantially impact both lapses32,35,36,37,38,39 and trial-history influences on decisions39,40. Together, these observations challenge the assumption that history biases and lapses have independent causes and raise the possibility that some of the variance ascribed to lapses emerges from history dependence.

In this work, we explore the idea that history biases reflect a misbelief about non-stationarity in the world, and demonstrate that normative decision-making under such beliefs gives rise to choices that are both history-dependent and appear to be evidence-independent (i.e. akin to lapses). This corresponds to an accumulation to bound process with a history dependent initial state. We fit this model to a large dataset of choices made by 152 rats trained on an auditory decision-making task. Despite heterogeneity in history biases and lapse rates in this population, we show that a substantial fraction of lapses can be explained by the presence of history dependence during evidence accumulation. Further, our model predicts the time it takes to make decisions. We test these predictions in a novel task in rats with reaction time reports, and show that it captures patterns of choices, reaction times, and their history dependence. This model significantly improves our ability to predict the temporal dynamics of decision variables within and across trials in perceptual decision-making tasks, rendering choices that were previously thought to be stochastic, predictable.

Results

A common mechanism produces history biases and apparent lapses

It is often assumed that well-trained subjects in two-alternative forced choice (2AFC) tasks have faithfully learnt the likelihood function and priors that determine the structure of the task23,41. Under this assumption, the optimal decision-making strategy entails combining any knowledge about prior prevalence of available options with the stream of incoming evidence until a desired threshold of confidence is reached in favor of one of the options41,42,43 (Fig. 1b top). This strategy converges to a drift-diffusion model (DDM) when evidence is sampled continuously23. In a DDM, one’s belief about the correct option maps onto a diffusing particle that drifts between two boundaries, where the first boundary the particle crosses determines the decision (Fig. 1b). Correspondingly, the initial state of this particle encodes the prior belief, and the drift rate is set by the likelihood of incoming evidence (Fig. 1b). We refer to the evolving state of the particle in this model as ‘accumulated evidence’.

However, in general, subjects may not know that the task structure is stationary, and might incorrectly assume that it is constantly changing19. In this case, even experienced subjects would not converge to a static estimate of prior probabilities and likelihood functions, but would instead continually update them from trial to trial. Here we consider choice behavior that results from non-stationary beliefs about priors, which result in trial-to-trial updates to the initial accumulator states. Although initial state updating is common to non-stationary beliefs in priors, likelihoods and reward functions, updates to the latter two additionally require drift rate updates (for a treatment of non-stationary likelihood functions which yield variability in drift rate, see14,44).

We assume that the initial state of the accumulator (I) is set based on the exponentially filtered history of choices and outcomes on past trials. Each unique choice-outcome pair (denoted by h; Fig. 1c) is tracked by its own exponential filter (ih). On each trial n, each filter ih decays by a factor of βh and is incremented by a factor of ηh depending on the choice-outcome pair on the previous trial:

{Rw, Lw, Rl, Ll} represent the possible choice-outcome pairs: right-win, left-win, right-loss, and left-loss respectively. on−1 is the choice-outcome pair observed on trial (n−1) and 1h(on−1) is an indicator function that is 1 when on−1 = h and is 0 otherwise. The initial state of accumulation, I on trial n is given by the sum of these individual exponential filters:

Such a filter can approximate optimal updating strategies under a variety of non-stationary beliefs. As an example, we show that this exponential filter can successfully approximate initial state updates during Bayesian learning of priors under the belief that the prior probabilities of the two hypotheses can undergo unsignaled jumps5,19 (Supplementary Fig. 1). Nevertheless, we use this more flexible parameterization to allow for asymmetric learning from different choices and outcomes, which could be beneficial under generative models where one believes that one category persists for longer than another (requiring different decay rates), or correct and incorrect outcomes are not equally informative (requiring different update magnitudes). For instance, in a prior-tracking experiment where previous correct choices had a cumulative effect, but errors had a resetting effect13, this could be captured in the exponential filter by faster decay rates for errors.

What are the consequences of such trial-by-trial updating of initial accumulator states for choice behavior? In a DDM, for a given initial state I and drift rate μ, the probability of choosing the option corresponding to bound B + is given by:

where B is the magnitude of the bound and σ2 is the squared diffusion coefficient (derived from Palmer et al.45). The resultant psychometric curves for different values of initial accumulator states are plotted in Fig. 1d. This expression reduces to a logistic function of μB/σ2 only when I = 0. Small deviations in the initial state largely resemble additive biases to the total evidence, shifting psychometric curves horizontally towards the option favored by the initial state. This corresponds to a change in the psychometric threshold i.e. the x-axis value at its inflection point (Fig. 1d lighter colors). Note that our use of the word “threshold” follows from Wichmann & Hill27, referring to the x-axis value at the inflection point, whereas we refer to the slope at this inflection point as “sensitivity”. Interestingly, large deviations in the initial state produce qualitatively different effects on choices (Fig. 1d darker colors). They not only bias the choices towards the option consistent with the initial state but additionally reduce the effective sensitivity to evidence. This can be seen as reduction in slope at the inflection point of the psychometric curve (Fig. 1d dashed lines) in addition to a change in threshold. Therefore, trial to trial deviations in the initial state produce history-biased choices which have differently diminished dependence on the evidence.

The average choice behavior obtained by pooling choices with different history-biased initial states is a mixture of psychometric curves with varying thresholds and sensitivity to perceptual evidence. Such a psychometric curve is heavy-tailed46,47 and appears to have asymptotic errors or “lapse rates” (Fig. 1e, black curve). These asymptotic errors are not truly evidence-independent, random decisions or true lapses, rather they are “apparent lapses” arising from evidence accumulation with deterministic history-based updates to the initial accumulator state. Importantly, these apparent lapses contribute to lapse rates when heavy-tailed psychometric curves are approximated by a logistic function. However, this approximation is bound to be inadequate if measurements were made for even higher stimulus strengths, making the heaviness of the tails even more evident. In such a setting, the psychometric curves obtained by conditioning on past trials’ choice and outcome, or history-conditioned psychometric curves, are both horizontally and vertically shifted, i.e. they show history-dependent modulations in both threshold and lapse rate parameters (Fig. 1e, Supplementary Fig. 2b). Furthermore, trial-history modulated lapse rates are uniquely produced by history-biased initial accumulator states (and therefore reflect apparent lapses), in contrast to lapse rates observed in the unconditioned psychometric curve which might have additional extraneous causes27,32,34, and therefore reflect both apparent and true lapses.

In this model, because history modulations of psychometric thresholds and lapse rates arise from one unified process, they are not allowed to vary independently of the decision-making process, or of each other. Rather their relative magnitudes are intimately coupled with and constrained by accumulation variables. For instance, increased magnitudes or timescales of initial state updating produce large fluctuations in the initial accumulator state across trials. This in turn reduces the effective sensitivity of the accumulation process to evidence, giving rise to more apparent lapses and history biases (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Similarly, changes in within-trial parameters of accumulation can dramatically influence these history modulations (Supplementary Fig. 2c). Decisions made with smaller accumulator bounds are more sensitive to initial state modulations, and therefore give rise to more apparent lapses and higher modulations of lapse rates and thresholds. Higher levels of sensory noise have a similar effect, yielding more apparent lapses, consistent with recent reports of lapse rates being modulated by sensory uncertainty32. Finally, impulsive integration strategies that overweigh early evidence rather than accumulating uniformly23 exaggerate the influence of initial states, producing more apparent lapses and history biases.

Some definitions:

Lapse rate: Lapse rates capture the difference between perfect performance and observed performance at the asymptotes, measured through sigmoidal fits to the psychometric curves.

True lapse: A true lapse is a stochastic, evidence-independent choice that arises from cognitive processes entirely separate from the decision process, such as inattention or motor error.

Apparent lapses: Apparent lapses are deterministic evidence-dependent choices, that nonetheless contribute to lapse rates when performance is averaged across trials.

Rats display varying degrees of history-dependent threshold and lapse rate modulation

We sought to test if the comodulations posited by our model are present in rat decision-making datasets, in order to ascertain whether a unified explanation could underlie the links between history biases and lapses.

We first examined whether and how rat decision-making strategies were affected by trial history. We analyzed choice data from 152 rats (37522 ± 22090 trials per rat, mean ± SD; Supplementary Fig. 3a) trained on a previously developed task that requires accumulation of pulsatile auditory evidence over time (‘Poisson Clicks’ task30). In this task, the subject is presented with two simultaneous streams of randomly-timed discrete pulses of evidence, one from a speaker to their left and the other to their right (Fig. 2a). The subject must maintain fixation throughout the stimulus, and subsequently orient towards the side which played the greater number of clicks to receive a water reward. The trial difficulty, stimulus duration, and correct answer were set independently on each trial. Because this task delivers sensory evidence through randomly but precisely timed pulses, it provides high statistical power to characterize decision variables that give rise to the choice behavior.

a Schematic of evidence accumulation task in rats: (Top): Phases of the ‘Poisson clicks’ task, including trial initiation in center port (left), evidence accumulation based on two streams of Poisson-distributed auditory clicks (middle) and choice report in one of two side ports followed by water reward for correct choices (right). (Bottom): Time-course of trial events in a typical trial. (Figure adapted with permission from Bingni W. Brunton et al., Rats and Humans Can Optimally Accumulate Evidence for Decision Making. Science 340,95-98(2013). DOI:10.1126/science.1233912) b Individual differences in history-dependence: Psychometric functions of three example rats from a large-scale dataset, displaying different kinds of history modulation. Choices are plotted conditioned on previous left (blue), right (pink) or all wins (black). (Left): Example rat with no history-dependence in choices, resembling the ideal observer. (Middle): Example rat with modulations of the threshold parameter alone, resembling the dominant conceptualization of history bias. (Right): Example rat with history-dependent modulation of both threshold and lapse rate parameter, similar to the majority of the population. Errorbars represent 95% binomial confidence intervals around the mean (n = [16946, 20577, 37523] trials for example 1, [8568, 9549, 18117] trials for example 2, [29358, 30821, 60179] trials for example 3 for psychometric curves conditioned on [right, left or all wins]) c Dataset displays significant modulations of both threshold and lapse rate parameters: Scatters showing parameters of psychometric functions following leftward wins (post left, blue) or rightward wins (post right, pink). Each pair of connected gray points represents an individual animal, solid colored dots represent average parameter values across animals. Trial history does not significantly affect the sensitivity parameter (top left) but significantly affects left, right lapse rate and threshold parameters (top right and bottom panels). (p = 0.8 for sensitivity, 3 × 10−17 for bias, 8 × 10−8 for left lapse, 6 × 10−7 for right lapse, two-sided Mann-Whitney U-test, n = 152) d Scatter comparing threshold and lapse rate modulations in the entire population (n = 152). Each dot is an individual animal, best-fit parameter values ± 95% bootstrap CIs. Black points represent example rats. The majority of the population lies in the top left quadrant, showing comodulations of both threshold and lapse rate parameters by history.

Rats performed this task accurately (0.79 ± 0.04, mean accuracy ± SD, Supplementary Fig. 3b). Performance was stable with little to no change in accuracy across trials (mean slope ± SD across rats of linear fit to hit rate over trials: 1.13 × 10−7 ± 8.90 × 10−7; Supplementary Fig. 3c) reflecting asymptotic behavior rather than task acquisition. Rats showed history dependence in their choices, largely tending towards a “win-stay, lose-switch” dependence (Supplementary Fig. 3e). We found substantial individual variability in the dependence of rats’ choices on history in the dataset. Some rats were weakly influenced by history (Fig. 2b left) while others showed a history-dependent modulation of the psychometric threshold parameter (Fig. 2b middle) or a history-dependent modulation of both threshold and lapse rate parameters (Fig. 2b right). The population as a whole most closely resembles Example rat 3, with both threshold and lapse rate parameters being significantly different following left and right wins while sensitivity is not affected (p = 0.8 for sensitivity, 3 × 10−17 for bias, 8 × 10−8 for left lapse, 6 × 10−7 for right lapse, two-sided Mann-Whitney U-test, n = 152 Fig. 2c). Using simulations, we confirmed that the logistic fits to psychometric curves can reliably recover performance asymptotes i.e lapse rates particularly in the parameter regimes of this dataset (Supplementary Fig. 4). As predicted by our model (Fig. 1e), trial-history biased both threshold and lapse rate parameters in the same direction (e.g. both biased toward rightward choices following right rewards). Moreover, the vast majority of rats show comodulations of both parameters by history (Pearson’s correlation coefficient: r = − 0.35, p = 7.28 × 10−6; Fig. 2d). Across rats, on average 17 ± 12% of lapses are modulated by trial history and therefore could potentially reflect apparent rather than true lapses (Supplementary Fig. 3d). These findings support the conclusion that rat decision-making strategies, while idiosyncratic, largely show history-dependent effects consistent with our model. Next, we tested the model more directly using trial-by-trial model fitting.

History-dependent initial states capture comodulations in thresholds and lapse rates in the data

To test whether the observed history modulations in thresholds and lapse rates arise from trial-by-trial updates to the initial accumulator state, we extended an accumulator model previously adapted to this pulsatile task30 to incorporate History-dependent Initial States (abbreviated as HISt, Fig. 3a). As before, we model this history-dependence using an exponential filter over past trials’ choices and outcomes (Fig. 1c). Hence, across trials the accumulator model with HISt produces apparent lapses, as well as coupled history modulations in psychometric threshold and lapse rate parameters.

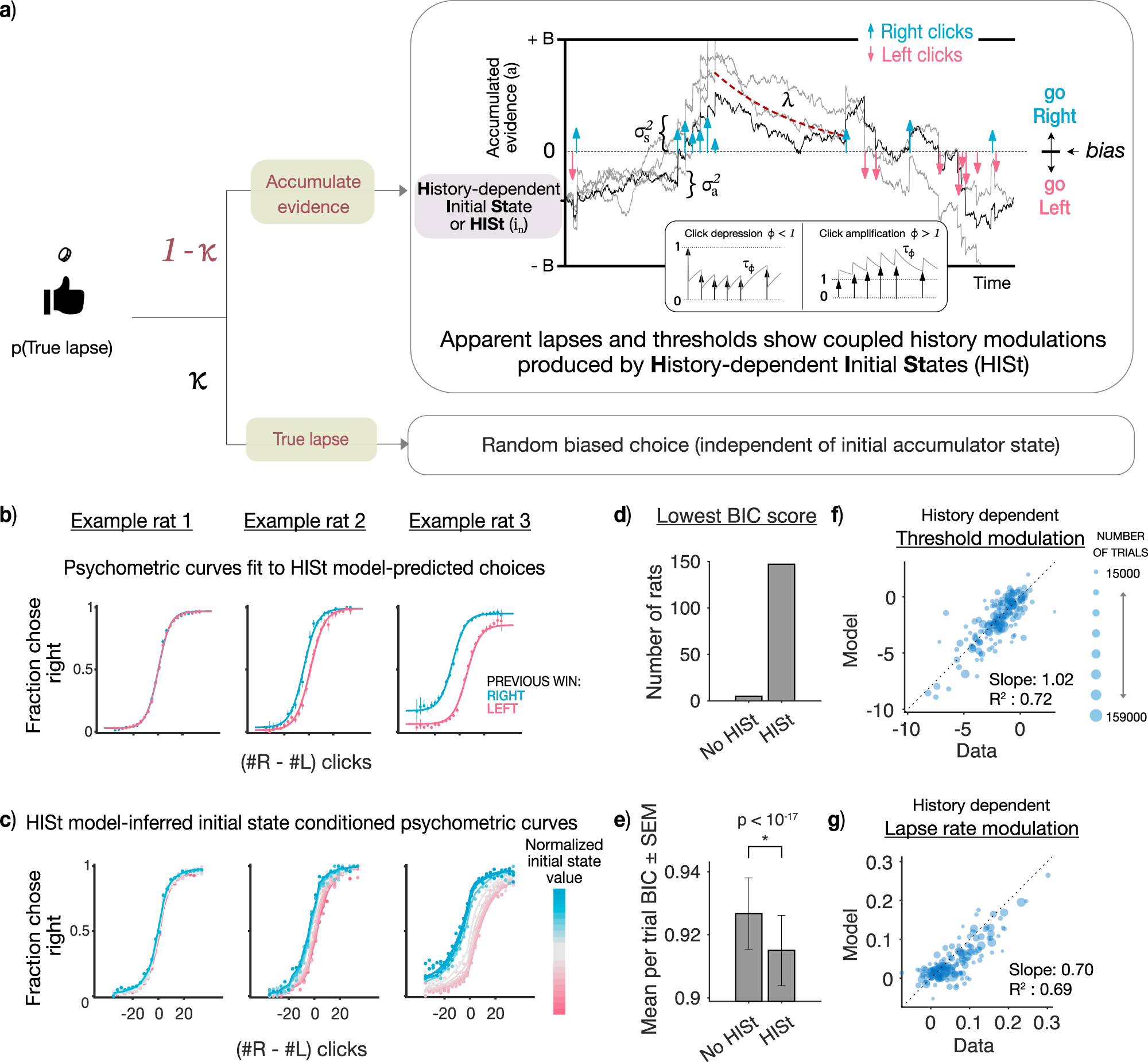

a Schematic of the model used to fit rat data in the Poisson Clicks task. (Top): The model consists of trial history-dependent initial states (HISt) that can produce history-dependent apparent lapses and threshold modulations. Additionally, the model consists of sensory noise (\({\sigma }_{s}^{2}\)) in click magnitudes, adaptation of successive click magnitudes based on an adaptation scale (ϕ) and timescale (τϕ), accumulator noise (\({\sigma }_{a}^{2}\)), leak in the accumulator (λ), and decision bounds +/–B30. (Bottom): On κ fraction of trials, the model chooses a random action with some bias (ρ) reflecting motor errors or random exploration. These true lapses are not modulated by history, such that any history modulations arise from the initial states alone. (Figure adapted with permission from Bingni W. Brunton et al., Rats and Humans Can Optimally Accumulate Evidence for Decision Making. Science 340,95-98(2013). DOI:10.1126/science.1233912) b Model fits to individual rats: Psychometric data (mean accuracy ± 95% binomial confidence intervals) from 3 example rats conditioned on previous rightward (blue) or leftward (wins), overlaid on model-predicted psychometric curves (solid line) from the accumulation with HISt model. (n = [16946, 20577] trials for example 1, [8568, 9549] trials for example 2, [29358, 30821] trials for example 3 for psychometric curves conditioned on [right, left wins]) c: Psychometric curves (solid line) from the same example rats conditioned on model-inferred initial states (colors from pink to blue). d Distribution of best fitting models for individual rats: e Model comparison using BIC by pooling per trial BIC score across rats and computing mean (n = 152). Mean of per trial BIC scores across rats were significantly lower for model with HISt (p = 9.85 × 10−18, one-sided paired t-test) indicating better fits. Error bars are SEM. For individual data points see Supplementary Fig. 6f Individual variations in history modulations captured by the accumulator model with HISt: History modulations of threshold parameters measured from psychometric fits to the raw data (x-axis) v.s. model predictions (y-axis). Individual points represent individual rats (n = 152), point sizes indicate number of trials. g same as (f) but for history-dependent lapse rate modulations.

Within a trial, our accumulator model leverages knowledge of the timing of each evidence pulse to model the sensory adaptation process as well as to estimate the noise and drift of the accumulator variable (Fig. 3a top bubble, Methods). The model includes a feedback parameter that controls whether integration is leaky, perfect, or impulsive. Following Brunton et al.30, this model also includes (biased) random choices independent of the accumulator value on a small fraction of trials (κ) - we consider decisions arising from this process to be “true lapses” because they are evidence-independent, unlike apparent lapses which still retain some evidence-dependence (Fig. 3a bottom bubble).

We performed trial-by-trial fitting of the accumulator model with and without History-dependent Initial States (HISt) to choices from each rat using maximum likelihood estimation (Methods). We find that the accumulator model with HISt captures both psychometric curve threshold and lapse rate modulations well across different regimes of rat behavior, as evident from fits to example rats (Fig. 3b). Moreover, conditioning rats’ psychometric curves on model-inferred initial state values reveals that the initial state captures a large amount of variance in choice probabilities (Fig. 3c), resembling theoretical predictions (Fig. 1c). This shows that the initial state is a key explanatory variable underlying choice variability both across and within individuals, that jointly modulates multiple features of the empirical psychometric curves in a parametric fashion. We used Bayes Information Criterion (BIC) to determine whether adding HISt to the accumulator model was warranted (Fig. 3d, e). Individual BIC scores recommended that adding HISt was warranted in 147/152 rats (Fig. 3d). This model also best captured choices across the population as a whole, with significantly lower mean BIC scores across rats (Mean per trial BIC score for HISt: 0.91 ± 0.01 vs. no HISt: 0.93 ± 0.01, p = 9.85 × 10−18, paired t-test; Fig. 3e). Next, we compared the psychometric threshold and lapse rate modulations produced by this model to the modulations in the data, as determined by conditioning the psychometric functions on trial-history (Fig. 3b). As predicted, the model successfully accounted for modulations in both these distinct psychometric features via the singular process of trial-by-trial history-dependent updates to the initial accumulator state. Next, we examined the extent to which these modulations were captured across individual rats (Fig 3f, g). We quantified these history modulations as follows: “threshold modulations" are defined as the horizontal distance between the midpoints of psychometric curves conditioned on previous wins and losses, and “lapse rate modulation" as the vertical distance between the asymptotes of these curves (Methods: History modulation of psychometric parameters, also see Supplementary Fig. 2b). This was done separately for model-predicted and rat choices and then compared. Across individuals, the model with HISt captured a substantial amount of variance [R2 = 0.72 (threshold parameter), R2 = 0.69 (lapse rate parameter)] and showed good correspondence to the empirical modulations in data [slope = 1.02 (threshold parameter), slope = 0.70 (lapse rate parameter)].

In our model, apparent lapses show history modulations since they are produced by history-dependent initial accumulator states, while true lapses do not since they result from an occasional flip in the final choice and are independent of the accumulator value (following Brunton et al.30). Such kinds of true lapses could reflect errors in motor execution or random exploratory choices made despite successful accumulation (Supplementary Fig. 5b). However true lapses could also occur due to inattention, i.e. an occasional failure to attend to the stimulus. In such cases, the optimal strategy devoid of sensory evidence is to deterministically choose the side favored by the initial accumulator state (Supplementary Fig. 5c). Therefore, inattentional true lapses, while remaining evidence independent, may nevertheless be modulated by history due to their initial state dependence. In order to account for this possibility, we fit an additional “inattentional” variant of the accumulator model with HISt (Supplementary Fig. 5a, c), and found that it was closely matched on BIC scores with the previous model which we label as the “motor error” variant (Supplementary Fig. 5e, f). Moreover, the inattentional variant, which additionally allows true lapses to depend on history, only captured slightly more variance in history modulations of lapse rates, at the expense of history modulations of thresholds (Supplementary Fig. 5d) while a variant of the model with inattentional true lapses but without HISt failed completely to capture the comodulation and performed much worse overall (Supplementary Fig. 6). Together these two findings support the hypothesis that apparent lapses produced by history-dependent initial states (rather than true lapses due to motor error or inattention) are the major driver of history-dependent comodulations in psychometric thresholds and lapse rates in the dataset.

To gain further insight into the initial state updating dynamics, we examined the fit parameters controlling the magnitude and timescale of updates (Supplementary Fig. 7). We found that across the population of rats, updates following wins and losses had similar magnitudes, but opposite signs, suggesting a tendency to repeat after wins and switch after losses. We compared these fits to those from a restricted version of the model whose initial state dynamics correspond to optimal updates in a Dynamic Belief Model48 (Supplementary Fig. 1) and found that about a third of the population (47/152 rats) were consistent with this form of statistical inference (Supplementary Fig. 7b). The remainder of the population did not show a significant correlation between post-win and post-loss parameters, consistent with a statistical model that treats wins and losses differentially13,49 (Supplementary Fig. 7c).

To summarize, our model predicted that the initial accumulator state should be the underlying variable that jointly drives history-dependence in thresholds and lapse rates – implying that our accumulator model with HISt should be able to simultaneously capture variability in both these parameters across rats. Our rat dataset strongly supports this prediction, lending evidence to the hypothesis that history-dependent initial states give rise to apparent lapses, and are the common cognitive process that underlie links between these two suboptimalities that were previously thought to be distinct from each other.

Reaction times support history-dependent initial state updating

In our model with history-dependent initial accumulator states, the time it takes for the accumulation variable to hit the bound determines the duration that the subject deliberates for, before committing to a choice. Therefore in addition to choices the model makes clear predictions about subjects’ reaction times (RTs). We sought to test if these predictions are borne out in subject RTs.

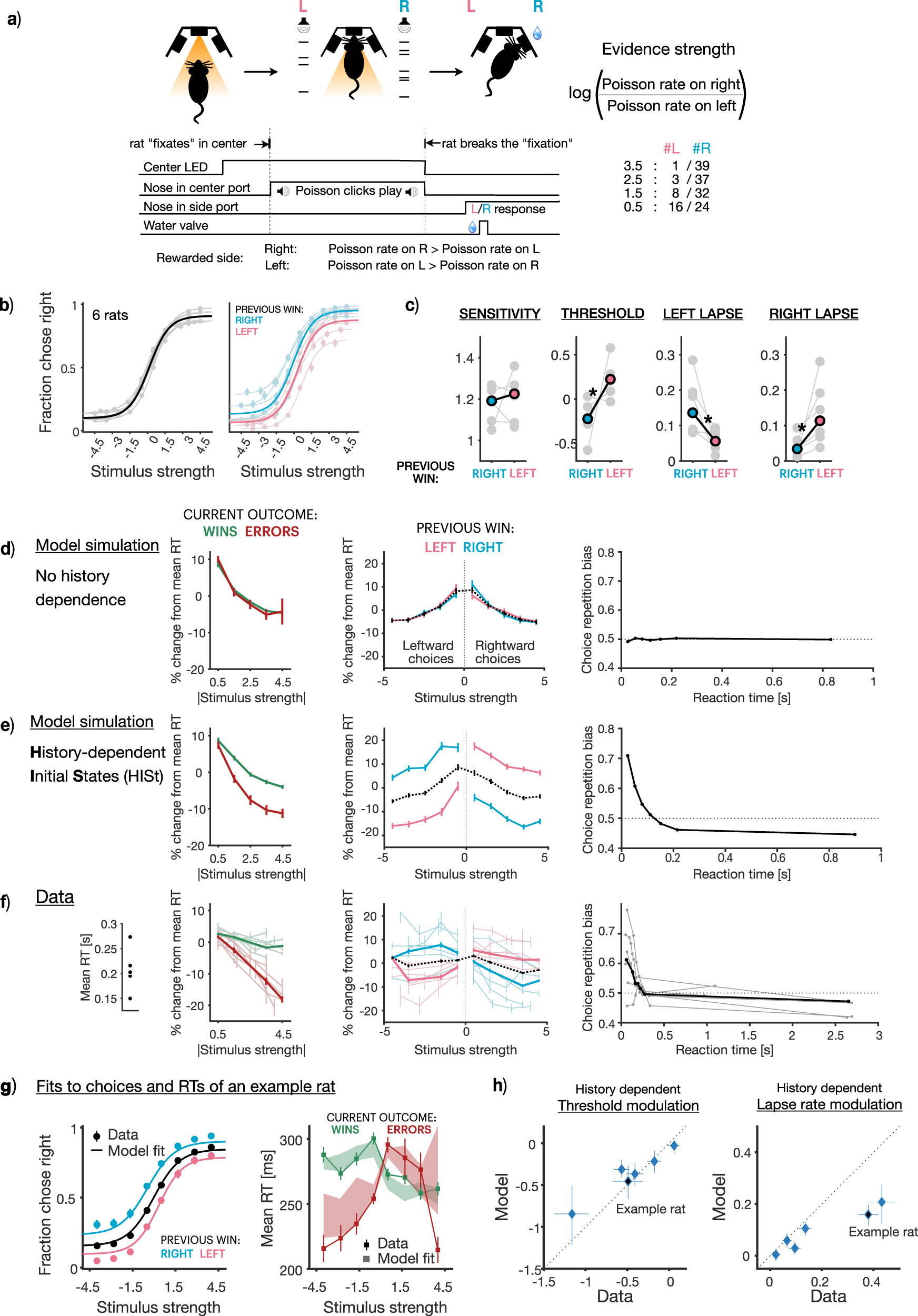

To this end, we trained rats (n = 6) on a new variant of the auditory evidence accumulation task, with two key modifications that allowed us to collect reaction time reports (Fig. 4a). First, in this new task the stimulus is played as long as the rat maintains their nose in the center port (or “fixates”) and stops immediately when this fixation is broken. Second, in this task the rat has to correctly report which speaker’s auditory click train is sampled from a higher Poisson rate to receive a water reward (unlike the non-reaction time task where the subject has to report the side which played the greater number of clicks). Rats perform this task with high accuracy (Fig. 4b left panel, average accuracy: 0.75 ± 0.02, number of trials 37205 ± 14247, mean ± SD). Similar to the previously analyzed data, their choices are impacted by recent trial history (Fig. 4b right panel). Moreover, trial-history dependent modulation of psychometric function parameters (Fig. 4c) resembles that of the non-reaction time task (Fig. 2c; p = 0.69 for sensitivity, 0.004 for threshold, 0.02 for left lapse rate, 0.02 for right lapse rate, Mann-Whitney U-test). Once again, this history modulation of both psychometric threshold and lapse rate parameters in tandem is consistent with our singular accumulator model with history-dependent initial states.

a Schematic of reaction time task in rats (Figure adapted with permission from Bingni W. Brunton et al., Rats and Humans Can Optimally Accumulate Evidence for Decision Making. Science 340,95-98(2013). DOI:10.1126/science.1233912) b Average choice behavior on all trials (left; n = 223231 trials) and following previous right (n = 86109 trials) or left wins (n = 82678 trials; right) across 6 rats (solid line), overlaid on individual rat behavior (translucent lines). Errorbars represent 95% binomial confidence intervals around the mean. c Average parameters (solid points) of history-conditioned psychometric curves, overlaid on individual parameters (translucent points) showing significant history modulations in threshold and lapse rate parameters (p = 0.69 for sensitivity, 0.004 for threshold, 0.02 for left lapse rate, 0.02 for right lapse rate, two-sided Mann-Whitney U-test; n = 6). d–f Reaction time signatures (d) expected from accumulator models with no history dependence in initial states, (e) expected from accumulator models with history-dependent initial states and (f) observed in data (n = 223,231 trials across all stimulus strengths and rats). (Leftmost column) error reaction times are expected to be shorter if initial states are history-dependent. Red (green) represents RTs on errors (wins). (Middle column) reaction times on trials following right wins (blue) are expected to be lower on rightward stimuli (positive half of x-axis), and similarly following left wins (pink). (Rightmost columns) repetition biases in choices are expected to occur more frequently for short reaction times, when the effect of initial states is strong. Error bars represent SEM. g Joint fits of the accumulator model with history-dependent initial states to choices (left) and reaction times (right) of an example rat (n = 24413 trials). Data represented by points (circles: choices, mean accuracy ± 95% binomial confidence intervals; squares: reaction times, mean RT ± SEM) and model fits represented by lines (choices) or shaded bars (reaction times, thickness represents 95% bootstrap prediction intervals). Reaction times (right) are split by wins (green) or errors (red). h Scatter plot showing correspondence between history modulations in threshold (left) or lapse rate (right) parameters derived from data (x-axis) and model fits (y-axis). Individual points represent individual rats (n = 6), best-fit parameter values ± 95% bootstrap CIs.

Moreover, RTs of these rats display several signatures predicted by our model (Fig. 4d–f). First, trial-to-trial variability in

Popular Products

-

Long Pin Slicker Brush for Dogs Groom...

Long Pin Slicker Brush for Dogs Groom...$60.99$41.78 -

Pet Grooming Shedding Brush Comb

Pet Grooming Shedding Brush Comb$10.99$6.78 -

Adjustable Cat Muzzle Anti Bite Scrat...

Adjustable Cat Muzzle Anti Bite Scrat...$44.99$30.78 -

Automatic Cat Water Fountain with Ste...

Automatic Cat Water Fountain with Ste...$78.99$54.78 -

Automatic Cat Feeder & Water Dispense...

Automatic Cat Feeder & Water Dispense...$87.67$54.00