A Renal Clearable Fluorogenic Probe For In Vivo β-galactosidase Activity Detection During Aging And Senolysis

Abstract

Accumulation of senescent cells with age leads to tissue dysfunction and related diseases. Their detection in vivo still constitutes a challenge in aging research. We describe the generation of a fluorogenic probe (sulfonic-Cy7Gal) based on a galactose derivative, to serve as substrate for β-galactosidase, conjugated to a Cy7 fluorophore modified with sulfonic groups to enhance its ability to diffuse. When administered to male or female mice, β-galactosidase cleaves the O-glycosidic bond, releasing the fluorophore that is ultimately excreted by the kidneys and can be measured in urine. The intensity of the recovered fluorophore reliably reflects an experimentally controlled load of cellular senescence and correlates with age-associated anxiety during aging and senolytic treatment. Interestingly, our findings with the probe indicate that the effects of senolysis are temporary if the treatment is discontinued. Our strategy may serve as a basis for developing fluorogenic platforms designed for easy longitudinal monitoring of enzymatic activities in biofluids.

Introduction

The design and development of new cost-effective and easily implementable diagnostic tools is an important goal in health1. In this context, diagnostic systems capable of detecting target biomarkers in readily accessible biofluids constitute a potential solution for non-invasive longitudinal studies2. An approach that fulfills these characteristics is the design of probes that can be specifically transformed in cells and tissues and have a rapid renal clearance thus allowing their detection in the urine. A few reports have described the use of multiplexed protease-sensitive nanoparticles that, in response to proteolytic cleavage in disease environments, release small reporter probes that can be measured in urine by mass spectrometry or immunoassays3,4. This approach has been elegantly exploited to detect acute kidney injury with fluorescent and chemiluminescent derivatives equipped with a (2-hydroxypropyl)-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD) moiety that promoted the renal clearance of the probes5,6. Another example describes a nanosensor based on ultra-small renally removable nanoparticles able to recognize deregulated proteases in cells. In this case, a colorimetric signal is indirectly detected by measuring the ability of the urine-recovered nanoparticles to oxidize a chromogenic peroxidase substrate in the presence of hydrogen peroxide7. These systems, however, rely on the application of complex and expensive analytical assays, or use nanoparticles which could result in undesired accumulation or side effects8. A reasonable alternative could be based on the use of a dye or fluorophore in an OFF state whose turning ON is dependent on the presence of a specific biomarker, such as an enzyme, that interacts with the probe at the site of the disease and that is chemically designed to favor its diffusion out of the cells and its filtration by the kidney into the urine. However, such a simple idea has not been widely exploited9,10.

Aging is characterized by a progressive and generalized functional decline and by the concomitant development of age-related diseases11. One of the hallmarks of aging is a rise in the frequency of senescent cells in most organs. Cells undergo senescence in response to several stressors, entering an irreversible cell cycle arrest that is accompanied by an increase in heterochromatin and in foci of DNA damage-responsive proteins, or DNA scars, increased levels of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor proteins p16INK4a (p16) and/or p21CIP1 (p21), and reduced levels of nuclear lamin B1. They also exhibit larger cell size and an augmented lysosomal compartment, with highly increased levels of the enzyme β-galactosidase (β-Gal)12. Senescent cells also display an intense secretory activity which appears to be involved in the pathophysiology of many aging related diseases through paracrine effects on neighbor healthy cells13,14. Senolysis, or the selective pharmacological killing of senescent cells, is thus being explored as a potentially promising intervention to promote tissue rejuvenation and health15,16. Within this context, there is a pressing need for strategies that focus on the in vivo identification of senescent cell load and its continual tracking over time, both in the aging process and following senolytic interventions17,18,19,20. Current non-invasive procedures rely primarily on the use of near-infrared fluorescence and MRI probes to detect increased β-Gal activity by in vivo imaging21,22,23,24.

Here, we report the design and synthesis of a cyanine-7-based probe and its ability to act as an in vivo read-out of β-Gal activity in biofluids without the necessity of imaging techniques. This probe consists of a Cy7 fluorophore modified with two SO3 groups and conjugated to a β-Gal substrate. Upon in vivo administration, the non-emissive sulfonic-Cy7Gal probe becomes hydrolyzed by β-Gal in cells to release the highly fluorescent dye sulfonic-Cy725. Subsequently, the fluorophore diffuses out of the cells and is quickly cleared at the kidneys, allowing its detection and quantitation in the urine. We show that the probe can be used to detect cell senescence in mice non-invasively and that it provides readouts during aging and senolytic intervention that correlate with age-associated anxious behavior. Interestingly, our in vivo studies reveal the transient nature of senolytic treatments. The swift optical determination of overall β-Gal activity through a simple urine measurement represents an attractive alternative to other procedures and enables easy longitudinal studies in aging research. Our results also indicate that the same strategy could be used to generate fluorogenic probes to monitor the activity of disease-related enzymes in easily collectable biological fluids in experimental animals and, eventually, in humans.

Results

Design and synthesis of a probe to monitor in vivo β-Gal activity in biofluids

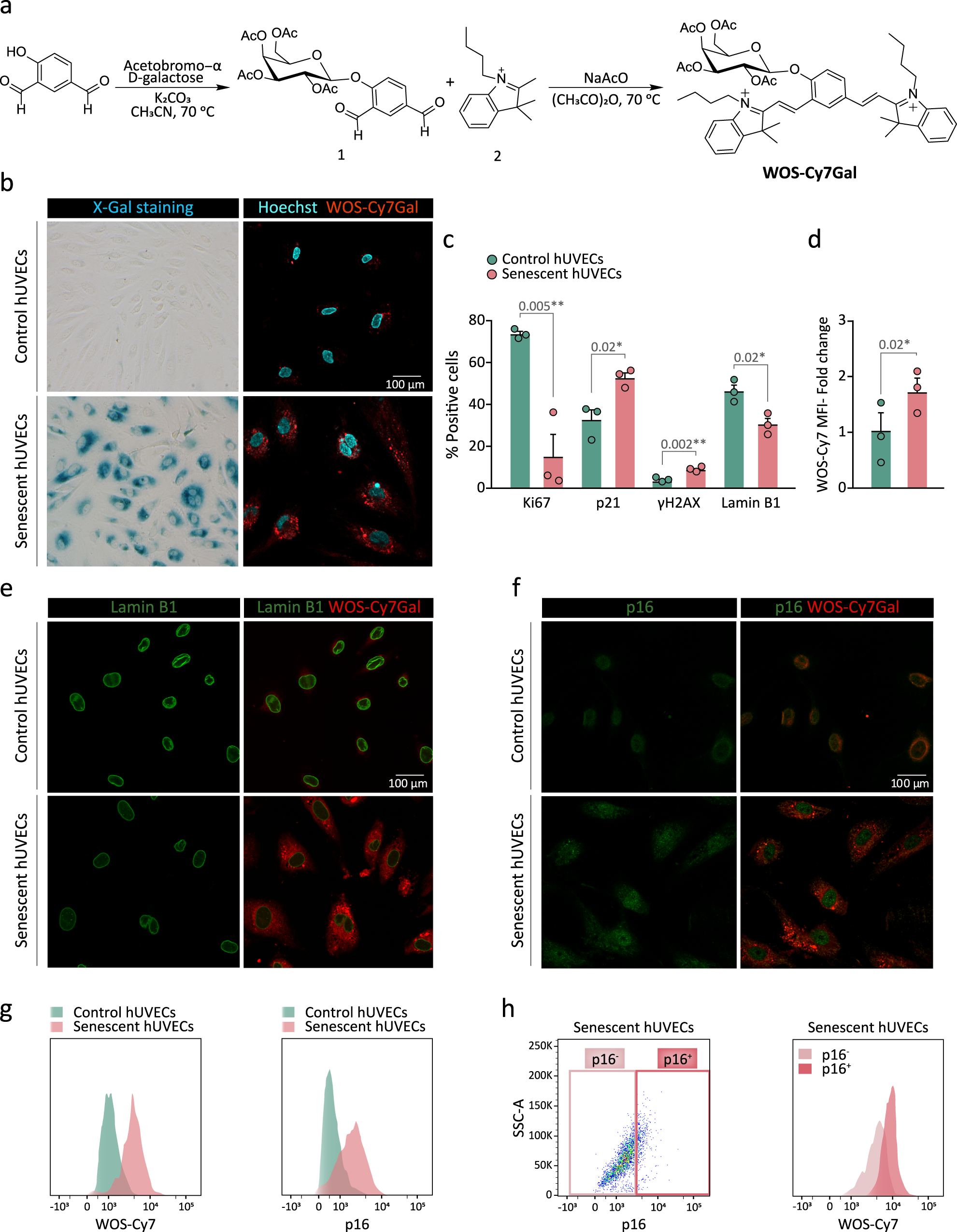

Fluorescent probes that are turned ON from an OFF state by the hydrolysis of an intramolecular O- or N-glycosidic bond by β-Gal at lysosomes have been previously generated by our group and others for detecting senescent cells19,21,24,26. Building on this work, we decided to develop a sulfonic-probe based on a Cy7 fluorophore skeleton modified with two SO3 groups and conjugated to a galactose derivative, with the idea that the addition of sulfonic groups to the releasable fluorophore would promote the diffusion out of the cells and its recovery in the urine when injected in vivo27. To pursue this goal, we first decided to synthesize the probe without this sulfonic modification to assess its value as a specific detector for β-Gal activity inside senescent cells. The probe without sulfonic groups (WOS-Cy7Gal) was prepared following a two-step synthetic procedure shown in Fig. 1a. First, 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-α-D-galactopyranosyl bromide was reacted with 4-hydroxyisophthalaldehyde in anhydrous acetonitrile yielding compound 1. Then, a Knoevenagel condensation between 1 and 1-butyl-2,3,3-trimethyl-3H-indol-1-ium iodide (2) yielded the WOS-Cy7Gal probe. Moreover, the WOS-Cy7 fluorophore was synthesized by protecting the hydroxyl group of 4-hydroxyisophthalaldehyde with t-butyldimethylsilyl chloride followed by a Knoevenagel condensation with 2 and the subsequent deprotection of the hydroxyl group. WOS-Cy7Gal and WOS-Cy7 were fully characterized by 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR, and HRMS (see Methods). PBS (pH 7) solutions of the WOS-Cy7 fluorophore showed an intense emission at ca. 660 nm (Φ WOS-Cy7 = 0.48) when excited at 580 nm, whereas PBS solutions of the WOS-Cy7Gal probe were poorly emissive at the same excitation wavelength (Φ WOS-Cy7Gal = 0.0076).

a Synthetic route used for the preparation of the WOS-Cy7Gal probe. b X-Gal histochemical staining (left) and confocal images of WOS-Cy7Gal (right) in hUVECs, treated with the senescence-inducing drug palbociclib (senescent) or not (control), for the determination of SA-β-Gal activity. c Phenotypic characterization of senescence in hUVECs by immunocytochemical detection of senescence-associated markers (n = 3 control and senescent cells). Note that senescent hUVECs showed a marked decrease in proliferation with lower Ki67 levels, a significant increase in the levels of p21 and DNA damage foci γH2AX, as well as a loss of lamin B1. d Quantification of WOS-Cy7Gal-associated median fluorescence intensity (MFI) in control and senescent hUVECs by flow cytometry (n = 3 control and senescent cells). The fold change refers to control hUVECs. e Confocal images of control and senescent hUVECs labeled with lamin B1 and WOS-Cy7Gal. Notice that senescent cells displayed lower fluorescence levels of lamin B1 and higher of the Cy7 fluorophore, compared to control ones. f Confocal images of control and senescent hUVECs labeled with p16 and WOS-Cy7Gal. Observe that senescent cells showed a brighter signal for both markers compared to control ones. g Flow cytometry histogram of the MFI of probe-released Cy7 and of p16, comparing control and senescent hUVECs. h Percentage of p16-/low and p16+/high senescent cells and flow cytometry histogram of WOS-Cy7Gal-associated MFI within these two cell populations. It is worth noting that the highest levels of fluorescence related to WOS-Cy7Gal corresponds to p16+/high cells. The graphs show the mean ± SEM. Unpaired and paired Student’s two-tailed t-tests were used for statistical analysis in graphs c and d, respectively. The number of independent biological samples (represented as dots) used and the exact p-values are indicated in the graphs. Scale bars: 100 μm. Source data is provided as a Source Data file.

In order to validate the ability of WOS-Cy7Gal to monitor cell senescence, we tested the probe in cultures of primary venous endothelial cells obtained from the human umbilical cord (hUVECs) treated with 1 µM palbociclib, a CDK4/6 inhibitor that reportedly induces cell cycle arrest and senescence28. Treatment with the drug for 7 days resulted in enlargement of the cells, which exhibit a more flattened morphology and nuclear alterations, in agreement with morphological features described for senescent phenotypes29. The induction of cell senescence was corroborated by increased β-Gal activity in the X-Gal histochemical reaction (Fig. 1b). Treated cells ceased proliferation (Ki67-negative) and exhibited increased levels of DNA damage (γH2AX-positive foci) and p21 protein and lower levels of lamin B1, all cell senescence features12 (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 1a). Pharmacologically-induced senescent hUVECs were strongly positive for WOS-Cy7-emission after 10 min in the presence of the probe (Fig. 1d). Likewise, we could detect the emission of the probe when these cells reached replicative senescence after 29 passages (Supplementary Fig. 1b, c). Our results indicated that WOS-Cy7Gal is an appropriate probe to monitor senescence in cells.

Subsequently, we set out to correlate the probe detection with well-established markers of cell senescence at the single cell level. Given that the β-Gal enzyme is still active after fixation, we formaldehyde-fixed palbociclib-treated and untreated hUVECs before the immunostaining for p16 and lamin B1. Next, we applied WOS-Cy7Gal and monitored its emission signal after only 10 min. Increased levels of emission from punctate structures resembling lysosomes in the senescent cells were found to co-label with apparently lower lamin B1 levels and higher p16 levels (Fig. 1e, f). To establish a quantitative correlation between p16 and probe-related fluorescent levels, we immunostained fixed cells in suspension with antibodies to p16 and then exposed the cells to WOS-Cy7Gal for 10 min, and both fluorescent emissions were monitored 15 min afterwards by flow cytometry. We observed that the cells with higher levels of p16 were also brighter for the WOS-Cy7 emission (Fig. 1g, h), indicating that the WOS-Cy7Gal probe can be a reliable indicator of senescence-associated β-Gal activity.

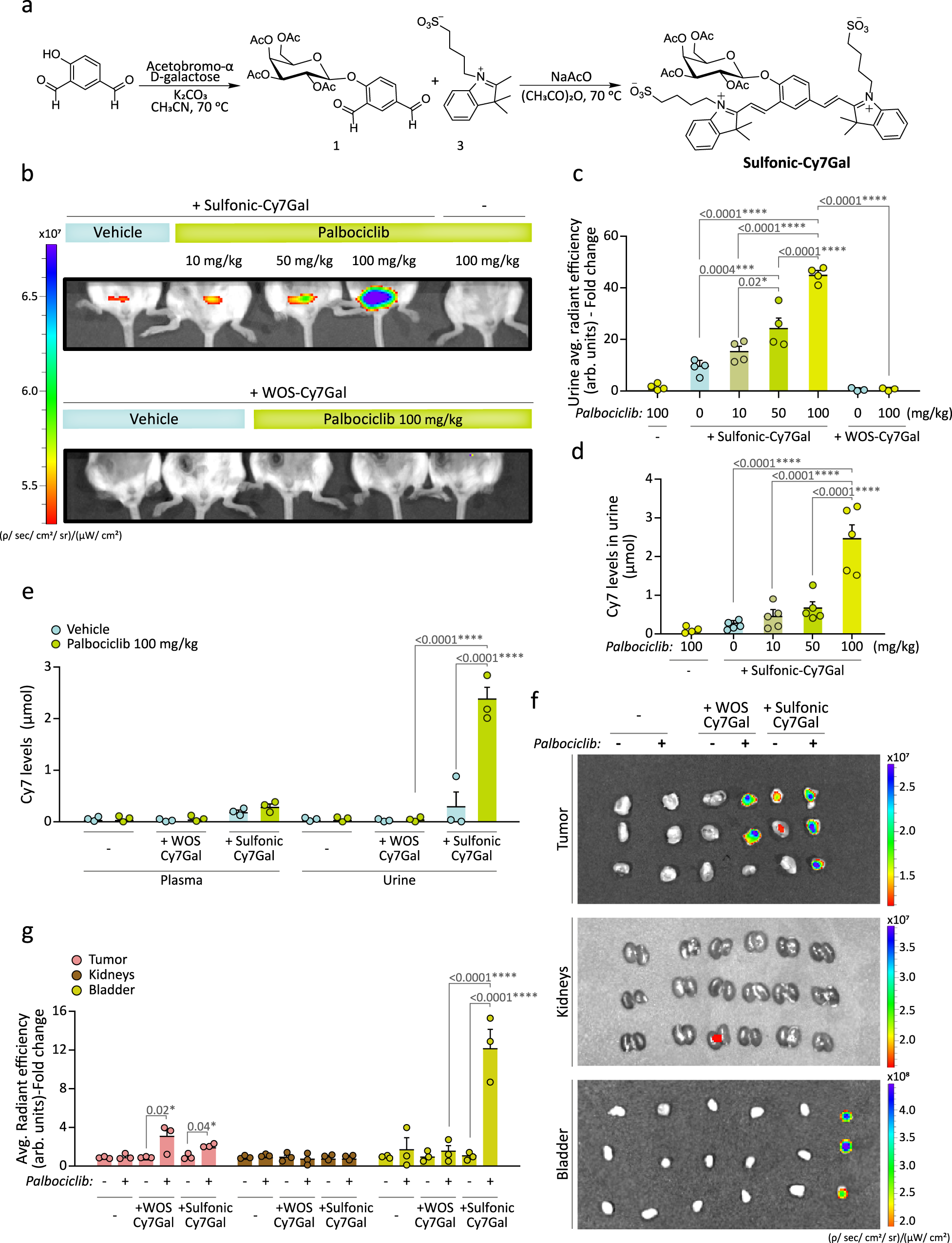

We next synthesized the same probe with sulfonic groups added. A Knoevenagel condensation between 1 and, in this case, 1-(4-sulfobutyl)−2,3,3-trimethylindolium inner salt (3) yielded the sulfonic-Cy7Gal probe (Fig. 2a). The sulfonic-Cy7 fluorophore was synthesized in the same manner as in the case of WOS-Cy7. The probe and the fluorophore were fully characterized by 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR, and HRMS (see Methods section). PBS (pH 7) solutions of the sulfonic-Cy7 fluorophore showed an intense broad emission band centered at ca. 660 nm (ΦCy7 = 0.43) when excited at 580 nm, whereas PBS solutions of the sulfonic-Cy7Gal probe were poorly fluorescent at the same excitation wavelength (ΦCy7Gal = 0.0062) (Supplementary Fig. 2a). The fluorescence emission intensity of sulfonic-Cy7 fluorophore remained unchanged in the 5-10 pH range (Supplementary Fig. 2b, c). The hydrolysis of sulfonic-Cy7Gal in PBS solutions in the presence of the β-Gal enzyme was studied by HPLC. The chromatograms showed the disappearance of the sulfonic-Cy7Gal peak and the appearance of sulfonic-Cy7 if the enzyme was present (Supplementary Fig. 2d). The specificity and selectivity of the probe for β-Gal were further tested by incubation of sulfonic-Cy7Gal with different enzymes and with interfering species, such as cations, anions, and small peptides (Supplementary Fig. 2e). Only β-Gal induced a marked emission enhancement at ca. 660 nm due to the hydrolysis of sulfonic-Cy7Gal. Interestingly, an enhanced emission was observed when the sulfonic-Cy7Gal was incubated in the presence of both esterase and β-Gal, but not esterase alone (Supplementary Fig. 2e). The signal increase is likely due to the hydrolysis of the acetate moieties in the sulfonic-Cy7Gal probe by esterases prior to the rupture of the O-glycosidic bond by β-Gal, a sequence that is expected to happen intracellularly. Both sulfonic-Cy7Gal and WOS-Cy7Gal yielded brighter emission in naturally senescent vs. replication-competent hUVECs in culture but, as expected, the signal with sulfonic-Cy7Gal exhibited a more diffuse cellular pattern that was compatible with lower retention in lysosomes (Supplementary Fig. 2f, g).

a Synthetic route used for the preparation of the sulfonic-Cy7Gal probe, carrying sulfonic groups. b At the top, in vivo IVIS® imaging of sulfonic-Cy7Gal-associated fluorescence in bladders of BALB/cByJ female mice bearing 4T1 mammary tumors and orally treated with palbociclib (0, 10, 50, 100 mg/kg), compared to mice treated with the highest dose of palbociclib but non-injected with the probe. At the bottom, the same animal model injected with the WOS-Cy7Gal probe, comparing those receiving 100 mg/kg of palbociclib to untreated mice. c IVIS® readout of sulfonic-Cy7 average radiant efficiency in urine from mice under the conditions described in b (n = 4 for sulfonic-Cy7Gal injected-mice, n = 4 for non-probe-injected mice and n = 3 for WOS-Cy7Gal injected-mice). Note that the level of fluorescence increases in urine as a function of palbociclib dose. The fold change refers to untreated sulfonic-Cy7Gal-injected mice. d Quantification of the amount (μmol) of sulfonic-Cy7 fluorophore excreted in urine by fluorometer measurements after i.p. injection of sulfonic-Cy7Gal, using a calibration curve ’(n = 5 biologically independent animals). e Quantification of the fluorophore recovered after i.p. injection of sulfonic-Cy7Gal or WOS-Cy7Gal in urine and plasma from mice bearing 4T1 tumors and treated or not with palbociclib (100 mg/kg) using a fluorometer and a calibration curve (n = 3 biologically independent animals). See that only the probe carrying sulfonic groups is rapidly recovered in urine. f Ex vivo IVIS® imaging of tumors, kidneys and bladders from breast tumor-bearing mice, treated or not with 100 mg/kg of palbociclib, and injected or not with WOS-Cy7Gal and sulfonic-Cy7Gal. g Readout of the probes-associated fluorescence with IVIS® in the organs and experimental conditions exposed in image f (n = 3 biologically independent animals). The fold change refers to untreated mice for each organ and probe. Fluorescence (average radiant efficiency) associated with each ROI is measured in arbitrary units (arb.units). The graphs show the mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison post-hoc tests were used for statistical analysis. Source data is provided as a Source Data file.

To evaluate whether sulfonic-Cy7Gal could indeed provide a reliable readout in urine of cell senescence in vivo, we used it in mice in which the senescent cell burden could be experimentally manipulated. To this end, we decided to produce grafts of a controlled number of senescent cells using the 4T1 mouse mammary tumor cell line, a cellular model of triple negative-breast cancer that is sensitive to palbociclib-induced senescence30,31,32. We first corroborated that 4T1 cells enter senescence in vitro when treated with 5 µM palbociclib for 2 weeks as reported. The treatment resulted in increased β-Gal activity in the X-Gal histochemical reaction and higher levels of β-Gal protein in immunoblots (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Subsequently, control and senescent 4T1 cells were incubated with 20 µM sulfonic-Cy7Gal and analyzed by confocal microscopy 2 h post-incubation (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Neither control nor palbociclib-treated 4T1 cells exhibited any noticeable fluorescence signal in the absence of the probe when excited at 580 nm. After exposure to sulfonic-Cy7Gal, control 4T1 cells still displayed negligible fluorescence emission, whereas senescent 4T1 cells showed a 2.4-fold higher red emission that could be significantly reduced (ca. 60%) if cells were pre-incubated for 30 min with the β-Gal specific inhibitor D-galactose at 5 mM (Supplementary Fig. 3b). A marked reduction in the intensity was also found when the expression of Glb1, the gene that encodes lysosomal β-Gal, was interfered with a specific Glb1 siRNA (Supplementary Fig. 3c, d), indicating that β-Gal is responsible for the emission. Finally, viability assays indicated that the probe was innocuous for both normal and senescent cells (Supplementary Fig. 3e).

We next implanted orthotopic grafts of 1×106 4T1 cells into the left mammary fat pad of BALB/cByJ young female mice that were subsequently treated by daily oral gavage with 0, 10, 50, or 100 mg/kg palbociclib for 7 days to induce different degrees of cell senescence in the grafts. Tumors from mice treated with 10 mg/kg of palbociclib grew similarly to those in untreated mice, while tumors in mice treated with 50 or 100 mg/kg palbociclib displayed a significant reduction in volume, measured with a caliper (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Histological analyses indicated a progressively reduced proportion of Ki67-positive cells as the palbociclib dose increased, in line with its reported induction of cell senescence33,34, and increased β-Gal activity in the tumors, but not in organs such as liver or kidney (Supplementary Fig. 4b–d), providing us with a model of controlled cell senescence load in vivo. Next, mice bearing 4T1 tumors and treated with palbociclib at the different concentrations were anesthetized and intraperitoneally (i.p.) injected with 2.5 µmol of sulfonic-Cy7Gal or WOS-Cy7Gal. In vivo IVIS® imaging after 15 min revealed a detectable fluorescent signal in the bladders of mice injected with sulfonic-Cy7Gal, which increased with the palbociclib dosage (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 5a, b, for ROI selection and quantification in the bladder). The same amount of the WOS-Cy7Gal probe did not generate any fluorescent signal in the bladder of mice bearing 4T1 tumors and treated with 100 mg/kg palbociclib (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 5a, b, for ROI selection and quantification in the bladder). Urine subsequently recovered from the same animals was fluorescent only in those injected with sulfonic-Cy7Gal and also in a palbociclib dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 5c, d). Fluorometer measurements, relative to a sulfonic-Cy7 calibration curve, revealed a clear correlation of the sulfonic-Cy7 μmol levels un urine with the palbociclib dosage (Fig. 2d). In agreement with a swift renal clearance of the sulfonic-Cy7 fluorophore in animals injected with the sulfonic-Cy7Gal probe, we found a detectable amount of sulfonic-Cy7 in the urine (ca. 2.34 µmol) by fluorometer measurements, while the presence in plasma was significantly lower (0.33 µmol). In contrast, the WOS-Cy7 fluorophore was basically undetectable either in plasma (0.02 µmol) or urine (0.01 µmol) in animals injected with the WOS-Cy7Gal probe (Fig. 2e). A simple mass balance of the amount of sulfonic-Cy7Gal injected and that of sulfonic-Cy7 in urine measured allowed us to calculate that, on average, ca 95% of injected sulfonic-Cy7Gal was excreted through urine as sulfonic-Cy7 in palbociclib treated mice (100 mg/kg) while the excretion of WOS-Cy7 from WOS-Cy7Gal was negligible (ca 1%).

To corroborate the results at the organ level, we analyzed ex vivo the tumors, the kidneys and the bladder of those mice treated with 100 mg/kg palbociclib after euthanasia. In these autopsy samples, both probes gave a positive signal in the tumors (Fig. 2f, g), in accordance with their capacity to detect senescent cells. In contrast, we could detect a strong fluorescent signal in the bladder only in the animals injected with the sulfonic-Cy7Gal probe (Fig. 2f, g). The lack of an equivalently strong signal in the kidneys suggests a rapid clearance of the fluorophore, in line with previously shown results in plasma (Fig. 2e). Additional postmortem analyses in the tumors and different organs of the animals treated with increasing palbociclib doses and injected with the sulfonic-Cy7Gal indicate that the progressive rise in the fluorescence in urine derives from the experimentally produced senescence load in the tumors (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b). Our results together demonstrate that sulfonic acid moieties promote a rapid renal clearance of the Cy7 fluorophore upon cleavage of the sulfonic-Cy7Gal probe by the β-Gal enzyme.

The sulfonic-Cy7Gal probe is a reliable urine detector for the aging-associated increase in β-Gal activity

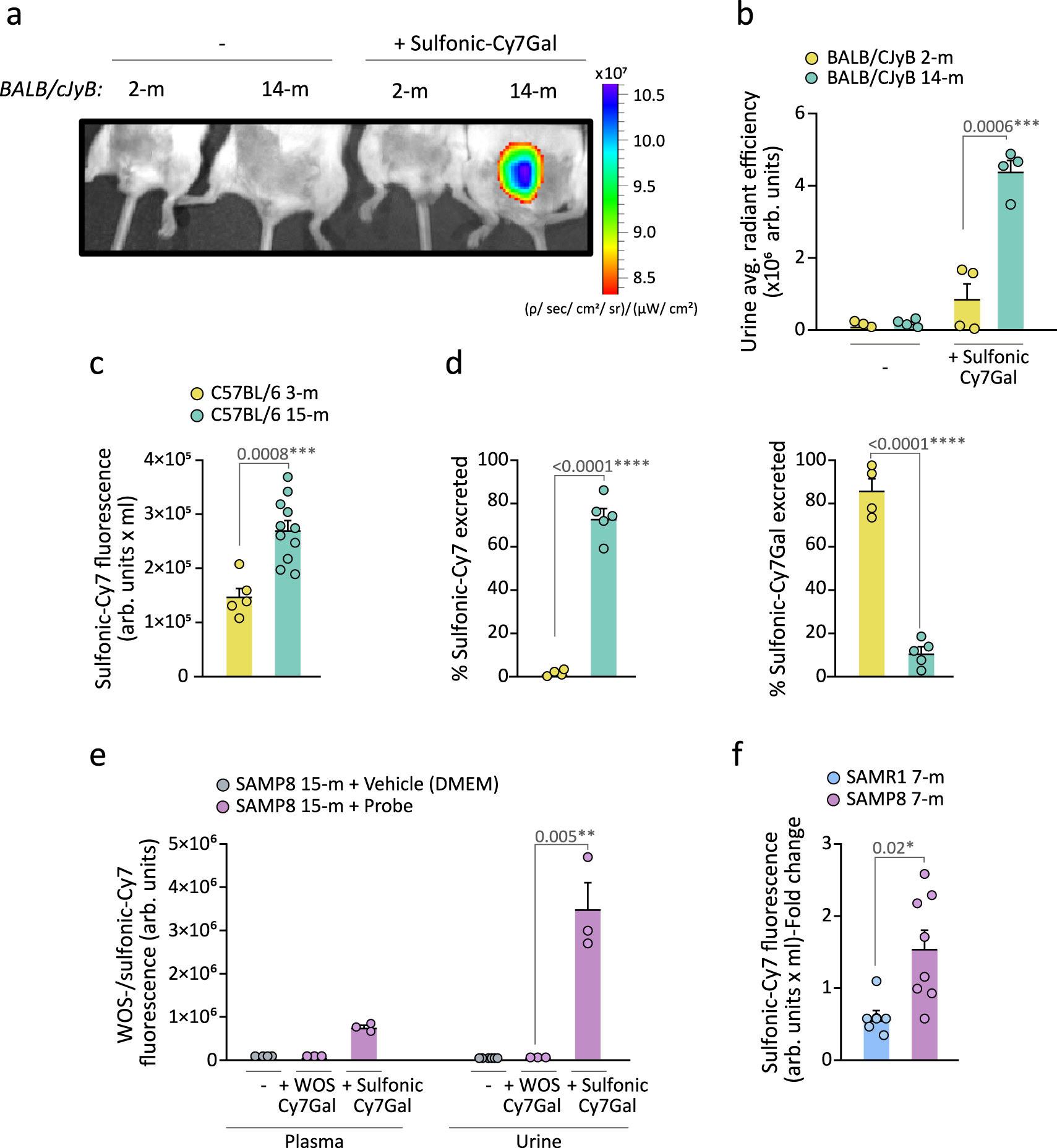

We next aimed to test the potential of the sulfonic-Cy7Gal probe for monitoring overall β-Gal activity during aging by i.p. injecting it in healthy 2- and 14-month-old (m) BALB/cJyB mice. IVIS® images of the anesthetized mice 15 min post-injection revealed fluorescence accumulation in the bladder of 14-m, but not 2-m mice (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 7a, b for ROI selection and quantification in the bladder). The fluorescent signal detected by IVIS® imaging in the urine collected from elderly mice was 5.2-fold stronger than from young mice (Fig. 3b), in agreement with an expected higher systemic β-Gal activity in old animals13. After euthanasia, the bladder, brain and lungs were studied also by IVIS® imaging. Quantification of the emission intensity revealed a 5.2-fold increase in the bladder of aged vs. young mice and increases of 2.3 and 2.7-fold for brain and lungs, respectively, in aged mice when compared to young animals (Supplementary Fig. 7c–e). The latter is in agreement with increases in cell senescence incidence in lungs reported with aging35. In the brain, β-Gal activity is not a specific marker of senescence, as many healthy neurons have large lysosomal compartments36. Interestingly, senescent-like neurons and glial cells have been identified in mouse models of neurodegeneration and in neuropathological human tissue37,38. The apparent capacity of the probe to permeate the blood-brain barrier, however, opens the possibility to study global β-Gal activity, including that of the brain. Furthermore, aging-associated endothelial cell senescence can increase BBB permeability39 potentially contributing to the use of the probe for studies in brain aging and neurodegeneration. Because renal function can vary depending on the mouse strain40, we also tested the sulfonic-Cy7Gal probe in mice of the C57BL/6 strain and found again higher fluorescence in the urine from old 15-m animals relative to 3-m younger counterparts by fluorimeter-based detection (Fig. 3c). Direct measurement of the relative levels of the probe and the released fluorophore in the urine by HPLC indicated that most of the sulfonic-Cy7Gal probe is excreted intact in young animals (ca. 80%) whereas the sulfonic-Cy7 fluorophore is the major species excreted in aged mice (ca. 75%) (Fig. 3d). These results were indicative of the potential of the sulfonic-Cy7Gal probe to monitor aging.

a In vivo IVIS® imaging of bladders from 2- and 14-m BALB/cByJ mice injected or not with the sulfonic-Cy7Gal probe. b IVIS® readout of sulfonic-Cy7 fluorescence in urine from 2- (n = 4) vs. 14-m (n = 4) BALB/cByJ mice. c Fluorometer measurement of sulfonic-Cy7 associated fluorescence in the urine of 3- (n = 5) and 15-m (n = 11) C57BL/6 mice. Note that this value is multiplied by the total volume of urine recovered (arb.units x mL) to avoid variability in micturition between young and old mice that may alter the concentration of the fluorophore in the bladder and the measurement of fluorescence in urine. d Measurement of the percentage of sulfonic-Cy7Gal or sulfonic-Cy7 excreted in the urine of 3- (n = 4) vs. 15-m (n = 5) C57BL/6 mice by HPLC. e Fluorescence readout of urine and plasma samples from 15-m SAMP8 mice (n = 3) after i.p. injection of WOS-/sulfonic-Cy7Gal compared to vehicle-injected SAMP8 mice (n = 3) using a fluorometer. f Fluorometer measurement of sulfonic-Cy7 fluorescence in the urine of 7-m SAMP8 (n = 8) and SAMR1 mice (n = 6). Fold change is calculated relative to SAMR1 mice values. The graphs show the mean ± SEM. Unpaired Student’s two-tailed t-test was used for statistical analysis. The number of independent biological samples (represented as dots) used and the exact p-values are indicated in the graphs. Source data is provided as a Source Data file.

We decided to also use senescence accelerated mouse (SAM) strains which exhibit premature aging traits. A few decades ago, intensive inbreeding of AKR/J mice and selection for the early appearance of features such as hair loss, skin coarseness, and short life span, led to the isolation of senescence-prone (P) and senescence-resistant (R) series of mice which were crossed separately to establish the inbred SAMP and SAMR strains41. Relative to their genetic background-controls (SAMR1 mice), SAMP8 mice manifest several aging traits at earlier physiological ages41 and are widely used in aging research to study immune dysfunction42, osteoporosis43 or brain atrophy44. Injection of the sulfonic-Cy7Gal and WOS-Cy7Gal probes in 15-m mice of the SAMP8 background also resulted in the detection of fluorescence in urine, and in plasma to a lesser extent, only in animals treated with the renally-clearable probe (Fig. 3e).

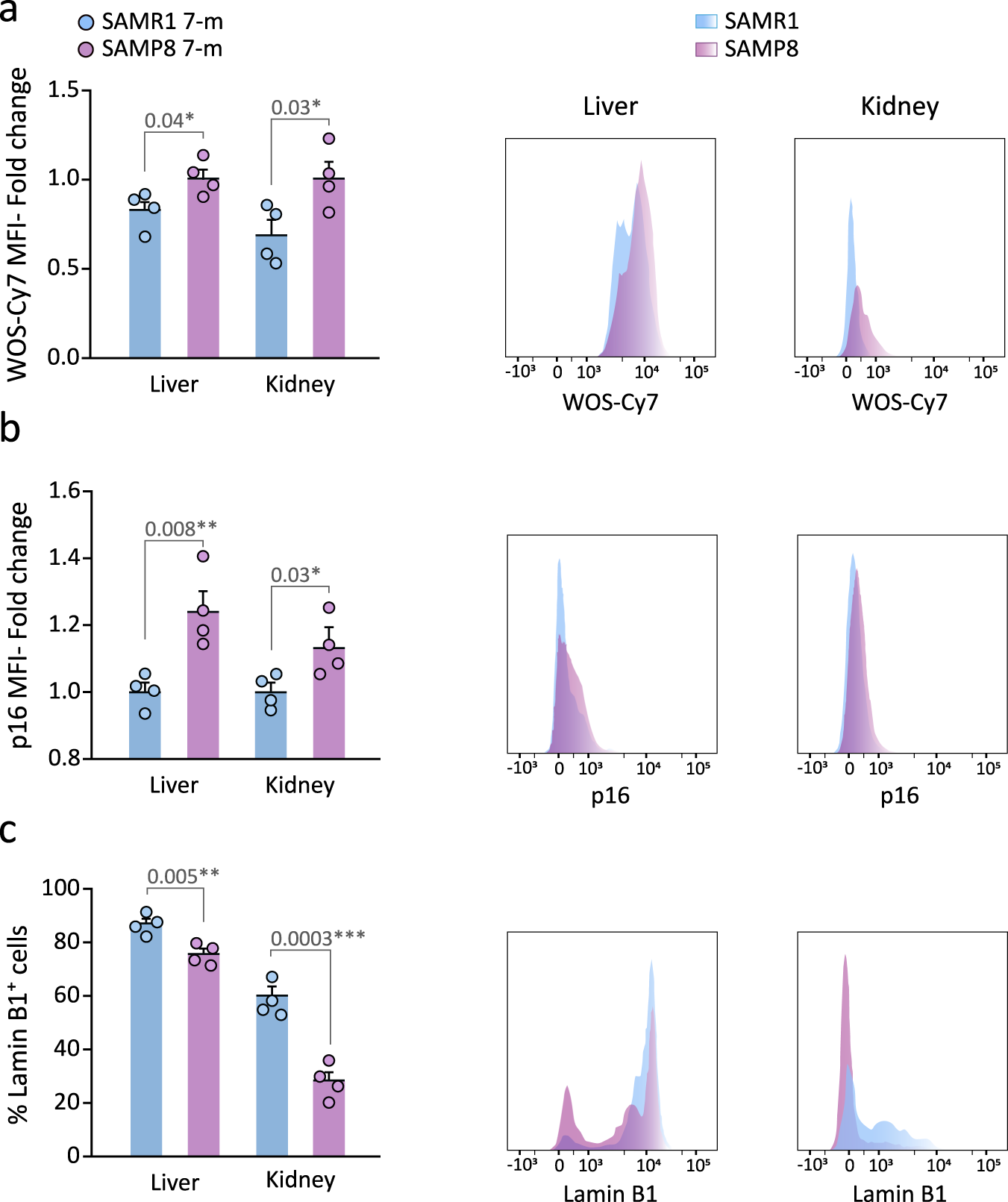

Because the age-related phenotypic differences between SAMP8 and SAMR1 mice begin to be evident after approximately 6 months of age45,46,47, we injected 7-m SAMR1 and SAMP8 mice with sulfonic-Cy7Gal and found a stronger fluorescent signal in the urine of SAMP8 vs. SAMR1 mice (Fig. 3f). We next decided to test whether the sulfonic-Cy7Gal probe could indeed be providing an in vivo readout of cell senescence, by comparing urine fluorescence with markers of senescence at the cell level in SAM mice. After euthanasia, we extracted the kidneys and livers, and their isolated cells were incubated ex vivo with the cell-trapped WOS-Cy7Gal probe or intracellularly immunostained for p16 or lamin B1 prior to their analysis by flow cytometry. In agreement with the levels of fluorescence in the urine of the animals, we found higher levels of β-Gal activity in SAMP8 vs. SAMR1 mice with the WOS-Cy7Gal probe (Fig. 4a). Likewise, we could observe higher proportions of cells with detectable levels of p16 and reduced levels of lamin B1 in cell dissociates from the organs of SAMP8 mice (Fig. 4b, c). These data indicated a good correlation between the end-point measurement of cell senescence with well-accepted markers and the in vivo global detection of β-Gal activity with the sulfonic-Cy7Gal probe in urine.

a Ex vivo flow cytometry analysis of β-Gal activity based on WOS-Cy7Gal-associated MFI in liver and kidney tissues of 7-m SAMP8 and SAMR1 mice and its histogram representation. b Ex vivo flow cytometry analysis of p16 MFI in liver and kidney tissues of SAMP8 and SAMR1 mice and representative flow cytometry histogram. c Ex vivo flow cytometry analysis of the percentage of lamin B1+ cells in liver and kidney tissues of SAMP8 and SAMR1 mice and representative histogram of lamin B1 MFI. Fold change is calculated relative to SAMR1 mice organs for each senescence marker. The graphs show the mean ± SEM. Unpaired Student’s two-tailed t-test was used for statistical analysis. The number of independent biological samples is n = 4 for SAMP8 and for SAMR1 mice. The exact p-values are indicated in the graphs. Source data is provided as a Source Data file.

The use of the sulfonic-Cy7Gal probe reveals that senolytic effects are transient

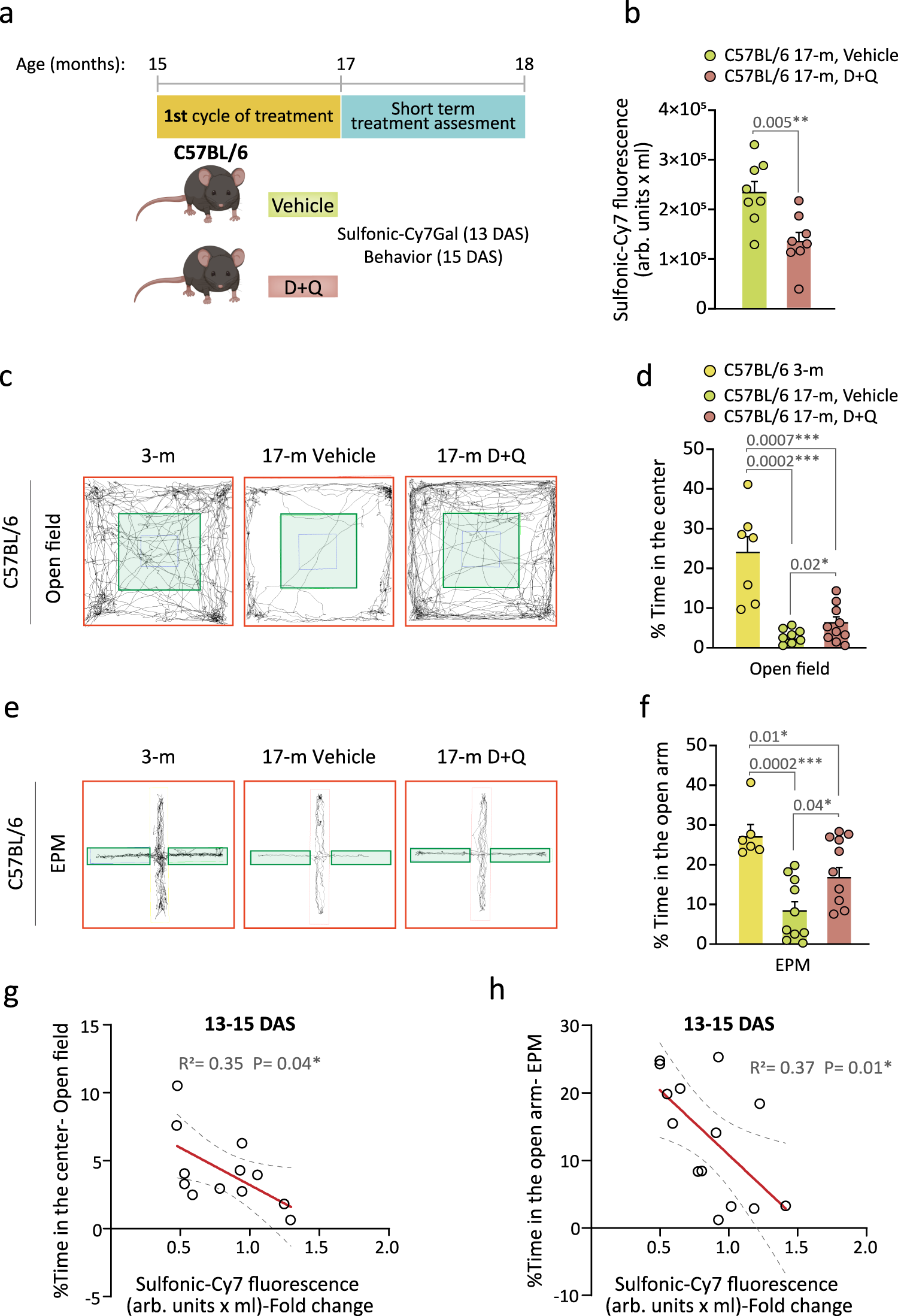

As the urine excretion of the sulfonic-Cy7 fluorophore enables longitudinal studies, we next set out to determine whether the sulfonic-Cy7Gal probe could be used to reliably monitor the effects of a senolytic treatment. Combination of dasatinib (D), an inhibitor of several tyrosine-kinases used as an anti-neoplastic agent for the treatment of acute lymphocytic leukemia, and quercetin (Q), a flavonoid that acts as an anti-apoptotic BCL-XL protein inhibitor, has shown efficacy in counteracting mechanisms of apoptosis evasion in senescent cells resulting in their selective elimination and subsequent beneficial effects in aged organs16,48. In our senolytic experiment, 15-m C57BL/6 mice were treated by oral gavage with two doses of D (5 mg/kg) + Q (50 mg/ml) or vehicle (20% PEG-n400 in saline solution) per week for 5 weeks and, 13 days after the end of the treatment, they were injected with the sulfonic-Cy7Gal probe (Fig. 5a). We could observe lower fluorescence levels in the urine of treated vs. untreated mice (Fig. 5b).

a Schedule of the senolytic treatment and its monitoring in C57BL/6 mice. 15-m mice received the senolytic drugs D + Q or the vehicle for 5 weeks and, 13 days after senolysis (DAS), the overall β-Gal activity was assessed with sulfonic-Cy7Gal as a measure of senescence burden. Two days later, anxious behavior was examined. b Sulfonic-Cy7 fluorescence measurement in the urine of 17-m C57BL/6 treated with D + Q (n = 8) or vehicle (n = 8). c Representative map of movement in the open field test comparing young (3-m) to old mice (17-m) that were treated or not with senolytic drugs. d Quantification of the percentage of the time that mice spent in the central area (green zone) of the open field, comparing mice aged 3- (n = 7) to 17-m treated with D + Q (n = 10) or vehicle (n = 8). e, Representative map of movement in the EPM test comparing young (3-m) to old (17-m) mice that were treated with vehicle or senolytic drugs. f Quantification of the percentage of time that mice spent in the open arm of the EPM, comparing mice of 3- (n = 6) and 17-m that were treated (n = 10) or not (n = 10) with D + Q. g Significant linear correlation between sulfonic-Cy7 fluorescence in urine and the percentage of time spent in the center of the open field in mice treated with D + Q (n = 5) or vehicle (n = 7). h Significant linear correlation between sulfonic-Cy7 fluorescence in urine and the percentage of time spent in the open arm of the EPM test in mice treated with D + Q (n = 6) or vehicle (n = 8). Fold change refers to sulfonic-Cy7 fluorescence levels in the urine of untreated mice in both correlation graphs. Graphs represent mean ± SEM. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis of the sulfonic-Cy7Gal fluorescence readout, one-way ANOVA for the assessment of anxious behavior and multiple linear regression to determine the relationship equation between both. P-values and the number of independent biological samples (represented as dots) are shown in the graphs. Source data is provided as a Source Data file.

The selected senolytic treatment reportedly alleviates brain phenotypes associated with aging and neurodegeneration49,50. Accordingly, as another non-invasive measure of the senolytic treatment, we decided to perform parallel behavioral tests that reportedly correlate with age-related declines in mice. Because an increase in anxiety is associated with aging and frailty, we used the open field and the elevated plus maze (EPM) tests to evaluate anxiety-related behavior. The open field test measures overall locomotor activity but also anxiety-like behavior as anxious mice typically avoid the lit central area and spend more time at the periphery of the open box, close to the walls. In the EPM, mice are confronted with the decision to spend time exploring the closed arms or the anxiety-generating open arms of an elevated maze51,52. As expected, the time spent in the central area of the open field or in the open arms of the EPM was significantly reduced in 17-m C57BL/6 mice when compared to young 3-m mice of the same strain (Fig. 5c–f). Regarding the senolytic experiment, the animals were tested for their performance in the open field and EPM tests 2 days after the measurement of the probe level in urine (Fig. 5a). The treatment resulted in improved performance of the elderly mice in both behavioral tests (Fig. 5c–f), reflecting lower anxiety after D + Q treatment. A group of 3-m mice was included as behavioral controls without changes in general locomotion (Supplementary Fig. 8). Importantly, we found a significant negative correlation between the sulfonic-Cy7 fluorescence levels in urine and the time spent in the central area of the open field or in the open arms of the EPM (Fig. 5g, h), indicating that animals with an organismal lower β-Gal readout display less anxious behavior. Interestingly, senescent cell clearance also alleviates obesity-induced anxiety53. These data suggested that sulfonic-Cy7Gal is sensitive enough to predict age-related behavior and, more importantly, that this probe can be used to monitor senolytic treatments in vivo.

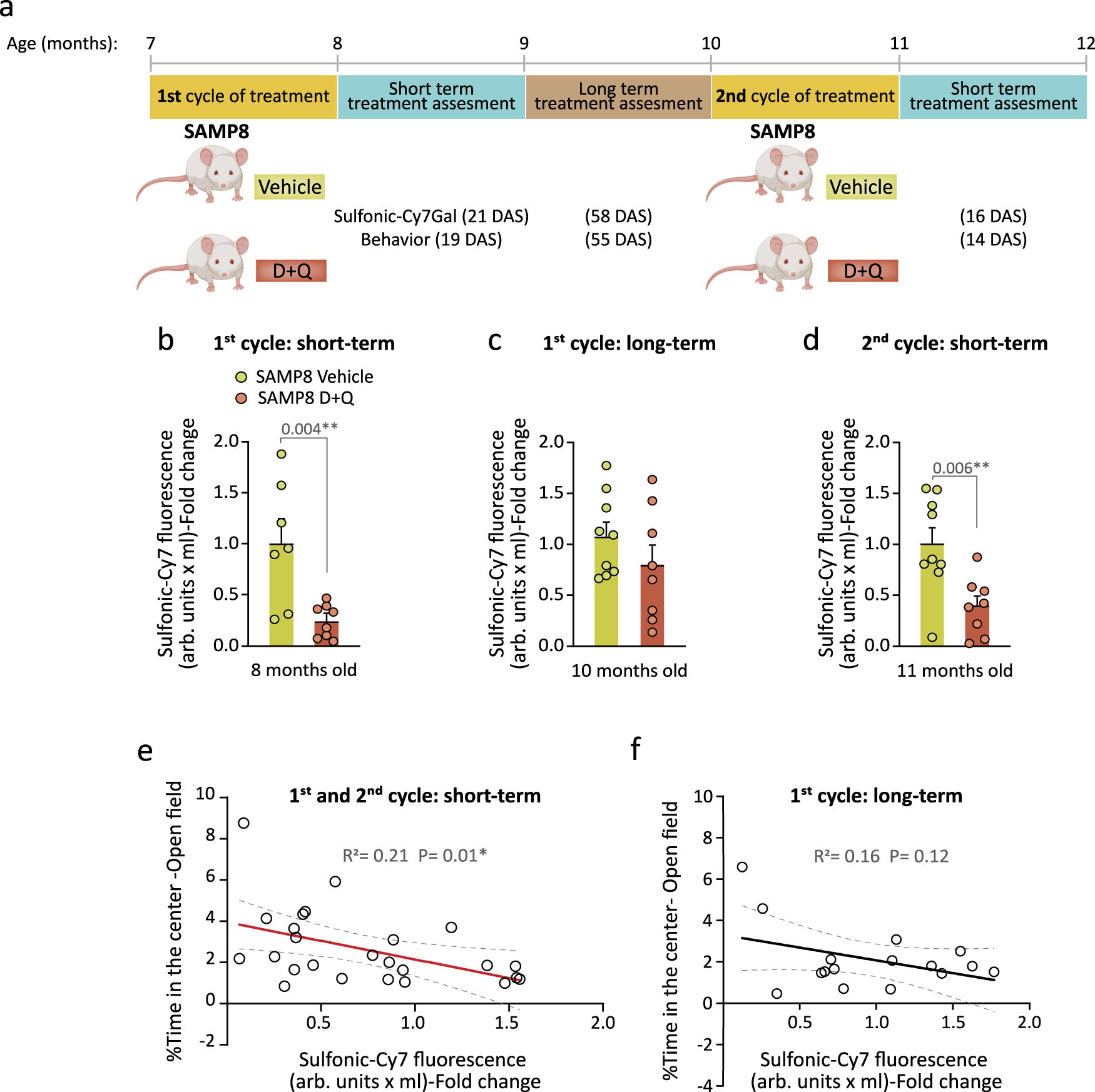

Next, we decided to test whether our probe could monitor intermittent senolytic treatment. Given that, in comparison with aged SAMR1 mice, the aged SAMP8 mice also show increased anxious behavior in the open field at ages when they still exhibit normal locomotion (i.e., 4 and 9-m) (Supplementary Fig. 9a–c)41,54, we exposed 7-m SAMP8 mice to the D + Q treatment for 5 weeks and evaluated fluorophore recovery in urine 21 days after cessation of the treatment (Fig. 6a). As before, we found that the treatment effectively decreased sulfonic-Cy7 levels in the urine (Fig. 6b; first cycle, short-term). A 3-day treatment with the drug combination did not change the behavior of 3-m SAMR1 control mice in the open field test, indicating that the D + Q drug combination per se does not affect anxiety (Supplementary Fig. 9d); however, we observed a decrease in anxious behavior when we assessed the animals at short-term after the senolytic treatment (Supplementary Fig. 9e, f), in line with the reduced sulfonic-Cy7 levels in the urine. We then repeated the measurements at 58 days post-treatment and found no differences in anxiety (Supplementary Fig. 9e) or urine fluorescence between animals treated with D + Q or vehicle (Fig. 6c; first cycle, long-term), suggesting that transient senolysis does not result in permanent alleviating effects. To make sure that the animals could still respond to senolysis, we treated the same animals once more and analyzed them at 16 days after the treatment, finding again the reduction in urine fluorescence (Fig. 6d; second cycle, short-term). As with naturally aged mice of the C57BL/6 strain, we could observe a significant negative correlation between levels of sulfonic-Cy7 fluorescence in urine and the time that SAMP8 mice spent in the central area of the open field test, but only in those short-term cases, i.e. in which the effect was measured less than 3 weeks after senolytic administration (Fig. 6e, f). In terms of sulfonic-Cy7Gal safety in vivo, 7 SAMP8 vehicle mice were injected at 7-m before the senolytic intervention and again at 8, 10 and 11-m for assessing the treatment. On the other hand, 6 C57BL/6 mice were injected with the probe at 15-m, before senolysis, and then at 17-m. All of them survived the entire senolytic longitudinal study, with no unforeseen health issues, until the moment of euthanasia at 12-m in SAMP8 and 18-m in C57BL/6 mice. In the absence of systematic toxicity assays in mice, these observations convey the idea that the probe is not overtly toxic for animals. Together, our data reveals that the probe reliably monitors senolysis and that the effects of D + Q wash off with time, in line with a treatment that eliminates senescent cells but does not eliminate the inductors of cell senescence.

a Schedule of the senolytic treatment and its monitoring in SAMP8 mice. At 7-m, SAMP8 mice received a first cycle of oral treatment with the senolytic drugs D + Q or vehicle, and anxious behavior (open field test) and senescence burden (sulfonic-Cy7Gal) were assessed shortly (first 21 DAS; first cycle, short-term) and long after this treatment (55-58 DAS; first cycle, long-term). In addition, a second cycle was carried out at the age of 10-m and sulfonic-Cy7Gal and behavior were analyzed within the first 16 DAS (second cycle, short-term). b Sulfonic-Cy7Gal-associated fluorescence measurement of urine samples from SAMP8 mice, administered with D + Q (n = 8) or vehicle (n = 7), 21 days after the first treatment cycle. c Sulfonic-Cy7Gal-associated fluorescence measurement of urine samples from SAMP8 mice, treated (n = 8) or not (n = 9) with D + Q, 58 days after the first treatment cycle. d Readout of sulfonic-Cy7Gal-associated fluorescence in urine samples from SAMP8 mice, treated with D + Q (n = 8) or vehicle (n = 9), 16 days after the second treatment cycle. e Significant linear correlation found shortly after treatment between the levels of sulfonic-Cy7 fluorescence in urine and the performance in the open field test of mice treated with D + Q (n = 10) or vehicle (n = 15). f No significant correlation was found between sulfonic-Cy7Gal and anxious behavior when assessed in the long term after the senolytic intervention (n = 8 for vehicles and n = 8 for treated mice). Fold change is calculated relative to sulfonic-Cy7 fluorescence in the urine of vehicle mice in all graphs. The graphs represent mean ± SEM. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis and multiple linear regression to determine the equation of relationship between sulfonic-Cy7 fluorescence in urine and the time mice spent in the center of the open field. Exact p-values and the number of independent biological samples (represented as dots) are shown in the graphs. Source data is provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

Geroscience is a very active field in biomedicine. Monitoring the rate of aging requires effective ways to measure systemic changes that can be used as biomarkers of decline progression. An increased prevalence of cell senescence seems to be linked to the deterioration of various organs, yet pinpointing exclusive markers for cell senescence remains a challenging endeavor. Among the available markers, lysosomal β-Gal enzymatic activity stands out as one of the most commonly used indicators of cell senescence12,55. Consequently, various probes have been recently devised to provide a means of detecting this state within isolated cells, biopsies, or whole organisms through imaging techniques17,18,19,20,

Popular Products

-

Oval Cat Scratcher Pad Bowl Nest and ...

Oval Cat Scratcher Pad Bowl Nest and ...$55.99$38.78 -

Dog Tuxedo Suit with Bow Tie and Leash

Dog Tuxedo Suit with Bow Tie and Leash$68.99$47.78 -

Washable Lint Remover Roller for Pet ...

Washable Lint Remover Roller for Pet ...$40.99$27.78 -

Automatic Rolling Cat Toy Ball for Pe...

Automatic Rolling Cat Toy Ball for Pe...$47.99$32.78 -

Walking Robot Plush Puppy Dog Toy

Walking Robot Plush Puppy Dog Toy$81.99$56.78